What Happens When The Bank Runs Out Of Money Great Depression

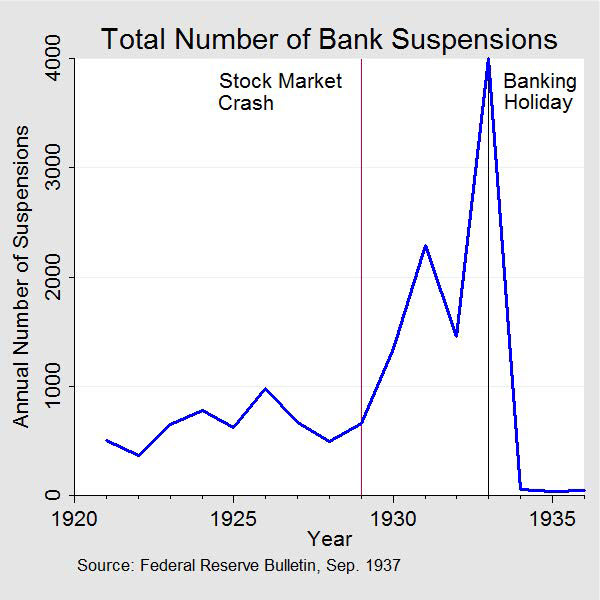

In the fall of 1930, the economy appeared poised for recovery. The previous three contractions, in 1920, 1923, and 1926, had lasted an average of fifteen months.oneThe downturn that began in the summer of 1929 had lasted for 15 months. A rapid and robust recovery was anticipated. In November 1930, nevertheless, a serial of crises amid commercial banks turned what had been a typical recession into the kickoff of the Great Depression.

When the crises began, over 8,000 commercial banks belonged to the Federal Reserve System, simply nearly sixteen,000 did not. Those nonmember banks operated in an environment similar to that which existed before the Federal Reserve was established in 1914. That environment harbored the causes of banking crises.

One cause was the do of counting checks in the process of collection every bit role of banks' greenbacks reserves. These 'floating' checks were counted in the reserves of ii banks, the one in which the cheque was deposited and the one on which the check was drawn.2In reality, still, the cash resided in only one depository financial institution. Bankers at the time referred to the reserves composed of float as fictitious reserves. The quantity of fictitious reserves rose throughout the 1920s and peaked only before the fiscal crisis in 1930. This meant that the banking arrangement as a whole had fewer cash (or real) reserves available in emergencies (Richardson 2007).

Another problem was the inability to mobilize banking company reserves in times of crisis. Nonmember banks kept a portion of their reserves every bit cash in their vaults and the bulk of their reserves as deposits in contributor banks in designated cities. Many, but not all, of the ultimate correspondents belonged to the Federal Reserve Organisation. This reserve pyramid limited country banks' access to reserves during times of crunch.3When a banking concern needed cash, because its customers were panicking and withdrawing funds en masse, the bank had to turn to its correspondent, which might be faced with requests from many banks simultaneously or might be beset by depositor runs itself. The contributor bank also might not have the funds on hand because its reserves consisted of checks in the post, rather than cash in its vault. If so, the contributor would, in plough, have to request reserves from some other contributor depository financial institution. That depository financial institution, in turn, might not take reserves bachelor or might not respond to the asking.4

These bug turned the collapse of Caldwell and Company into a painful financial event. Caldwell was a chop-chop expanding conglomerate and the largest fiscal belongings company in the S. It provided its clients with an assortment of services – banking, brokerage, insurance – through an expanding chain controlled by its parent corporation headquartered in Nashville, Tennessee. The parent got into trouble when its leaders invested likewise heavily in securities markets and lost substantial sums when stock prices declined. In order to cover their own losses, the leaders tuckered cash from the corporations that they controlled.

On November 7, one of Caldwell'southward principal subsidiaries, the Bank of Tennessee (Nashville) closed its doors. On November 12 and 17, Caldwell affiliates in Knoxville, Tennessee, and Louisville, Kentucky, too failed. The failures of these institutions triggered a contributor cascade that forced scores of commercial banks to append operations. In communities where these banks airtight, depositors panicked and withdrew funds en masse from other banks. Panic spread from town to town. Within a few weeks, hundreds of banks suspended operations. Most i-tertiary of these organizations reopened within a few months, but the majority were liquidated (Richardson 2007).

Panic began to subside in early December. But on December 11, the 4th-largest depository financial institution in New York City, Bank of The states, ceased operations. The banking company had been negotiating to merge with another institution. The New York Fed had helped with the search for a merger partner. When negotiations broke down, depositors rushed to withdraw funds, and New York's superintendent of banking closed the establishment. This event, like the collapse of Caldwell, generated paper headlines throughout the United States, stoking fears of financial panics and currency shortages like the panic of 1907 and inducing jittery depositors to withdraw funds from other banks.

The Federal Reserve's reaction to this crisis varied beyond districts. The crisis began in the Sixth District, headquartered in Atlanta. The leaders of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta believed that their responsibility as a lender of last resort extended to the broader banking arrangement. The Atlanta Fed expedited discount lending to member banks, encouraged member banks to extend loans to their nonmember respondents, and rushed funds to cities and towns beset by banking panics.five

The crisis also hit the Eighth District, headquartered in St. Louis. The leaders of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis had a narrower view of their responsibilities and refused to rediscount loans for the purpose of accommodating nonmember banks. During the crisis, the St. Louis Fed express discount lending and refused to assist nonmember institutions.

Outcomes differed between the districts. After the crisis, in the Sixth District, the economic wrinkle slowed and recovery began. In the 8th Commune, hundreds of banks failed. Lending declined. Business concern faltered and unemployment rose (Richardson and Troost 2009; Jalil 2014; Ziebarth 2013).

The banking crisis that began with the collapse of Caldwell subsided in early 1931. A new crunch erupted in June 1931, this time in the urban center of Chicago. In one case once again, depositor runs beset networks of nonmember banks, some of which had invested in assets that had declined in value. In Chicago, the trouble specially involved real manor.

These regional banking crises harmed the national economic system in several ways. The crises disrupted the process of credit creation, increasing the prices that firms paid for working capital and preventing some firms from acquiring credit at any toll (Bernanke 1983). This process was peculiarly pronounced in regions, like the Eighth Federal Reserve District, where large numbers of banks failed, and the data that those banks possessed most who in their community was a good and a bad credit adventure disappeared.

The crises also generated deflation because they convinced bankers to accumulate reserves and the public to hoard cash (Friedman and Schwartz 1964). Hoarding reduced the proportion of the monetary base of operations deposited in banks. Accumulating reserves reduced the proportion of deposits that banks loaned out. Together, hoarding and accumulating reduced the supply of coin, particularly the corporeality of coin in checking accounts, which at the time were the main ways of payment for goods and services. Every bit the stock of coin declined, the prices of goods necessarily followed.

Deflation harmed the economy in many means. Deflation forced banks, firms, and debtors into bankruptcy; distorted economical decision-making; reduced consumption; and increased unemployment. The aureate standard transmitted deflation to other industrial nations, which contributed to financial crises in those countries, and reflected back onto the Us, exacerbating a deflationary feedback loop.

The deflation ended with the Bank Holiday of 1933 and the Roosevelt administration's recovery programs. These programs included the suspension of the gold standard and the reflation of prices, discussed in essays on Roosevelt's Gold Program and the Golden Reserve Human activity of 1934, likewise as the reform of financial regulation, cosmos of deposit insurance, and recapitalization of commercial banks, discussed in essays on the Emergency Banking Human action, Banking Deed of 1933, and Cyberbanking Act of 1935.

Source: https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/banking-panics-1930-31

Posted by: meadeentinver93.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Happens When The Bank Runs Out Of Money Great Depression"

Post a Comment